Both Right. Both Wrong

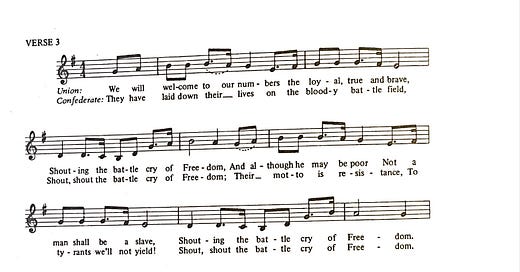

James M. McPherson begins his magnificent single volume history of the American Civil War “Battle Cry of Freedom” - Vol. 4 of the nine volume Oxford History of the United States - with the a reproduction of verse three of the hymn “The Battle Cry of Freedom” a popular song in the Civil War era on both sides of the conflict, in which each side had their own version to the tune. McPherson prefaces his history with the following observation:

“Both sides in the American Civil War professed to be fighting for freedom. The South, said Jefferson Davies in 1863, was ‘forced to take up arms to vindicate the political rights, the freedom, equality, and State sovereignty which were the heritage purchased by the blood of our revolutionary sires’. But if the Confederacy succeeded in this endeavor, insisted Abraham Lincoln, it would destroy the Union ‘conceived in Liberty’ by those revolutionary sires as ‘the last, best hope’ for the preservation of republican freedoms in the world. ‘We must settle this question now,’ said Lincoln in 1861, ‘whether in a free government the minority have the right to break up the government whenever they choose.’

Northern publicists ridiculed the Confederacy’s claim to fight for freedom. ‘Their motto’, declared the poet and editor William Cullen Bryant, ‘is not liberty, but slavery.’ But the North did not at first fight to free the slaves, ‘I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists,’ said Lincoln early in the conflict. The Union Congress overwhelmingly endorsed this position in July 1861. Within a year, however, both Lincoln and Congress decided to make emancipation of the slaves in Confederate States a Union war policy. By the time of the Gettysburg address in November 1863, the North was fighting for a ‘new birth of freedom’ to transform the Constitution written by the founding fathers, under which the United States had become the world’s largest slaveholding country, into a charter of emancipation for a republic where as the Northern version of ‘The Battle Cry of Freedom’ put it, ‘Not a man shall be a slave’.

James M. McPherson ~ Battle Cry of Freedom (1988 Oxford History of the United States)

The concept of two warring factions both appealing to the same high principle, be it God, Liberty or Nation, in justification of their aggression is as old as history itself. In the case of the American Civil War it is particularly interesting as both sides, devoutly Christian and devoutly committed to the principles of liberty enshrined in the Constitution, were building their principal justifications on wobbly foundations. In the case of the Confederacy, the gaping inconsistency was of course the morally indefensible slavery issue on which much of the wealth of the landowning classes depended and which required a very selective interpretation of the founding father’s disquisition of “inalienable rights” and a deliberate misreading of the words “all men” to their own peculiar economic advantage to pursue.

The Union’s inconsistency was I suspect more subtle in character, but, in my eyes more fundamentally insidious, based as it also was on a deliberate misinterpretation of a critical - some would argue the critical - tenet of the Constitution which recognises the rights of the individual States as being superior to that of the federation. The whole point of the Constitution was to confirm the legislative superiority of the individual States versus the “shared service centre” of the Federal government and through the State to enshrine the individual as the final arbiter of legislative authority, based as it was on the concept of those inalienable rights. Lincoln’s “leger de main” in heaving the whole “Union” and thereby that Union’s federal Government into a first place in the pecking order whilst sending in the troops to subjugate those who threatened to deny that reordering of constitutional priorities, was, one could argue the more fundamentally dangerous threat to liberty, the moral repugnancy of slavery notwithstanding.

Lincoln’s victory over the Confederacy through the military genius of Generals Grant and Sherman, his subsequent assassination and immediate beatification in the months following April 1865 papered over the constitutional inconsistency of his behaviour and substituted the “War on Slavery” as a (easily justified) moral imperative for the primary casus belli, more or less after the fact, with wholly predictable consequences for the expansion of the Federal Government in the US and indeed through the pre-eminience of the US as an economic and political empire in the past 159 years, the expansion of central governments everywhere.

As to who was on the right side and who on the wrong, the answer would be both, depending on which question you are seeking to answer.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pitchfork Papers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.